Today we are publishing a further 2 papers in our series of evidence reviews which consider important issues in relation to the ageing population. This time the reviews focus on retirement finances.

The effect of an ageing population on retirement

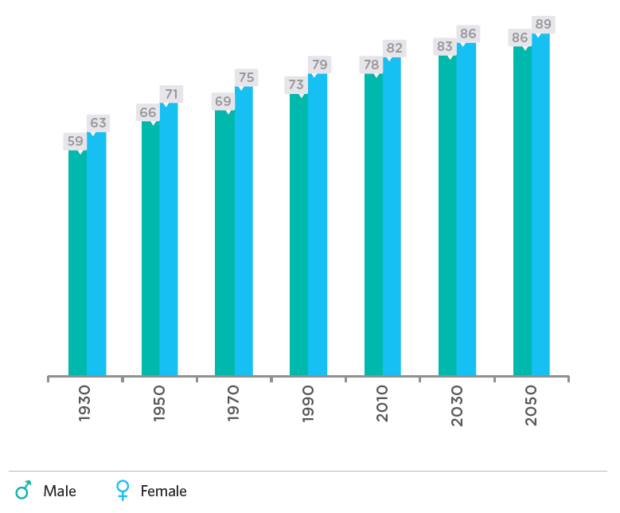

Average life expectancy is increasing at a faster rate than the state pension age (currently 65 for men and 60 for women, but expected to rise to 67 for both sexes by 2028). This means that future generations will have much longer retirements to support than their parents or grandparents might have had. How will younger generations ensure they have enough to support them in later life, and what will determine their success or failure? These are some of the questions considered by Abigail McKnight and Daniela Silcock in their papers on retirement savings and pensions.

Cohort-based estimates of average life expectancy – years

Can inheritance replace savings?

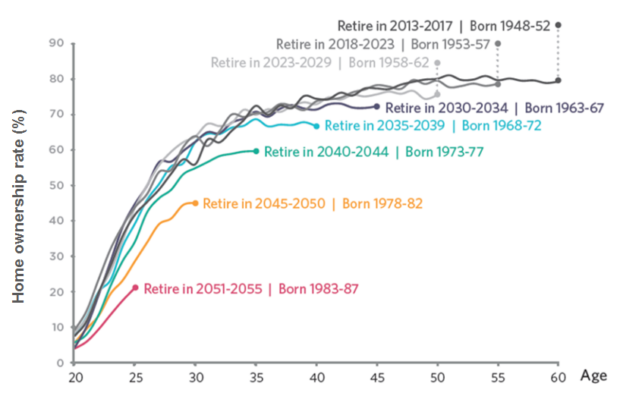

One of the trends identified in McKnight’s paper is for younger people to have less savings and less money tied up in assets (particularly housing – see below). Interestingly, this is not down to them having less money – the evidence shows that this trend has continued even when they are earning more than older generations. McKnight does not speculate about what this might say about society – although it is an intriguing thought for the reader – and instead she focuses on some of the financial factors that make younger generations less likely to save – higher rents and, crucially, an expectation of inheriting money from their parents and grandparents.

Home ownership rates by birth year and age

Will inheritance compensate the 2025 and 2040 cohorts (the focus of our project) for their lack of assets and savings? Although McKnight shows that there is evidence that they are more likely to inherit, the extent to which that justifies their reduced savings or lack of assets is difficult to ascertain. This issue, it seems, is tied up with some other crucial and unanswered questions about the future of the ageing population, not least whether the cost of their old age care will affect the amount of money that parents can bequeath.

Knowledge and responsibility

McKnight argues that there is no existing ‘definitive or ‘correct’ measure’ for defining the adequacy of people’s retirement savings – you can measure it against the average standards of living enjoyed by the working population, against the retirees' quality of life pre-retirement or against a minimum income standard. Calculating what people will need to save by 2025 or 2040 is even more challenging as we do not know how much people will have saved, how much they will have earned through their lifetime and what kind of living standard they will be expecting in retirement.

In the absence of an agreed methodology for calculating how much is needed to retire, you can imagine why it might be difficult for individuals to plan for the future. There is also the risk that people might not even understand the different types of pension and how they work (I would recommend Silcock’s explanation as a starting point).

Silcock makes it clear that knowledge is crucial to getting the most out of retirement savings. While as a society we are quite used to relying on things that we don’t understand – I know my iPhone won’t break if Siri realises I don’t have an electronics degree – Silcock identifies a direct correlation between financial literacy and the size of your pension income. I found that idea, that personal responsibility for retirement savings goes beyond just having a pension, really interesting and it is well worth reading the reviews in more detail to see what else they have to say about the balance of risks and responsibility in saving for the future.

Read the reports:

- Future of ageing: retirement income and assets (McKnight)

- Future of ageing: retirement income market (Silcock)

Featured image by Ken Teegardin on Flickr. Used under Creative Commons.

Sign up for email alerts from this blog, or follow us on Twitter.

Recent Comments