We have published another 6 papers in our series of evidence reviews examining important issues in relation to the ageing population. This time, they focus on the cultural and social factors that affect the ageing experience and attitudes towards it.

How the UK’s views on ageing compare with the rest of Europe

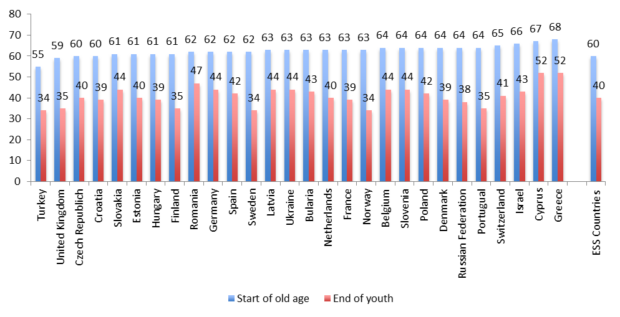

When does old age begin? Abrams, Swift, Lamont and Drury’s paper looks at attitudes to ageing across Europe and, surprisingly, find that countries have different answers to this apparently simply question.

What does this variation mean? The authors argue that is demonstrates that "the meaning of age is socially constructed" – in other words that how a society sees age is affected by far more than the biological fact of how old someone is.

‘The new old’ – changing attitudes and responsibilities in later life

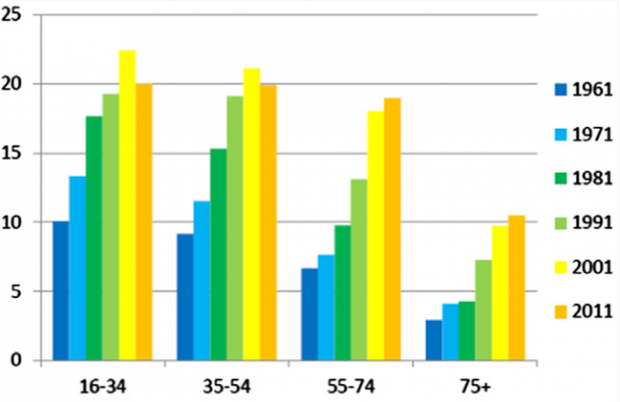

The way that people approach their own old age is changing, according to one review. Higgs and Gilleard identify a new generation of pensioners – 'the new old’, who reached adulthood in the 1960s and, the authors argue, increasingly see retirement as a period of opportunity (albeit with risks) because of the cultural and social change they have lived through.

Interestingly – they argue that one of the keys to this positive attitude is an increasing retention of consumer habits in later life – for example, the steady increase in how often older women shop for clothes.

This is significant, the authors argue, because "active consumerism provides a means for expressing social agency and choice, for going out into the world and choosing how one spends one’s time and money".

Damodaran and Olpert, whose papers focuses on technology, also find opportunities in later life. They argue that technology could completely change the ageing experience, with huge advances in everything from self-driving cars to, my personal favourite, robot assistants. However, while the potential for technology is huge, they also identify a range of misconceptions about how older people use it and argue that much more needs to be done to fully realise the benefits of these advances.

Ageism and care – the challenges facing older people

Although the reviews identify a range of exciting opportunities, there can be little doubt that older people still face real challenges in society’s attitudes towards them. The most significant of these is ageism, which Higgs and Gilleard strikingly describe as the single most prevalent form of discrimination in the UK, costing the economy £31bn a year.

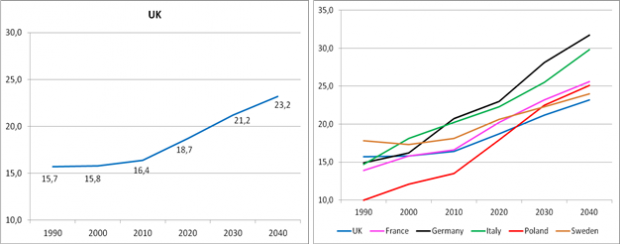

Worryingly, another review finds that this could get worse, as the proportion of older people increases. Kishita, Fisher and Laidlaw find that young adults anxious about their own ageing attribute to older people the negative stereotypes that they fear will describe them in the future. "As the UK’s society ages and younger people begin to see themselves as part of a smaller minority, this may become a more critical issue," the authors argue.

A final challenging result of this trend is increasing demand for care, identified in Hoff’s review of family care in the UK. He concludes that the number of formal and family carers will have to significantly increase in order to cope with demand. This could ask tough questions of how society treats its carers, and the authors recommendations in response are well worth a read.

Finally, Keating, Kwan, Hillcoat-Nalletamby and Burhol put this in the context of the relationships between different generations. Given the role that families play in providing care, the authors’ examination of the rights and wrong of our assumptions about family relationships – including families’ ability to absorb any added care burden in the future – feels hugely relevant to any conversation about society’s response to an ageing population.

Read the reports:

- Future of ageing: attitudes to ageing (Abrams, Swift, Lamont and Drury)

- Future of ageing: attitudes to ageing – social and cultural factors (Higgs and Gilleard)

- Future of ageing: attitudes to ageing – influence of new technologies (Damodaran and Olphert)

- Future of ageing: attitudes to ageing - psychological-factors (Kishita, Fisher and Laidlaw)

- Future of ageing: family care in the UK (Hoff)

- Future of ageing: relationships between the generations (Keating, Kwan, Hillcoat-Nalletamby and Burhol)

Featured image by B_Me. Used under Creative Commons.

Sign up for email alerts from this blog, or follow us on Twitter.

Recent Comments